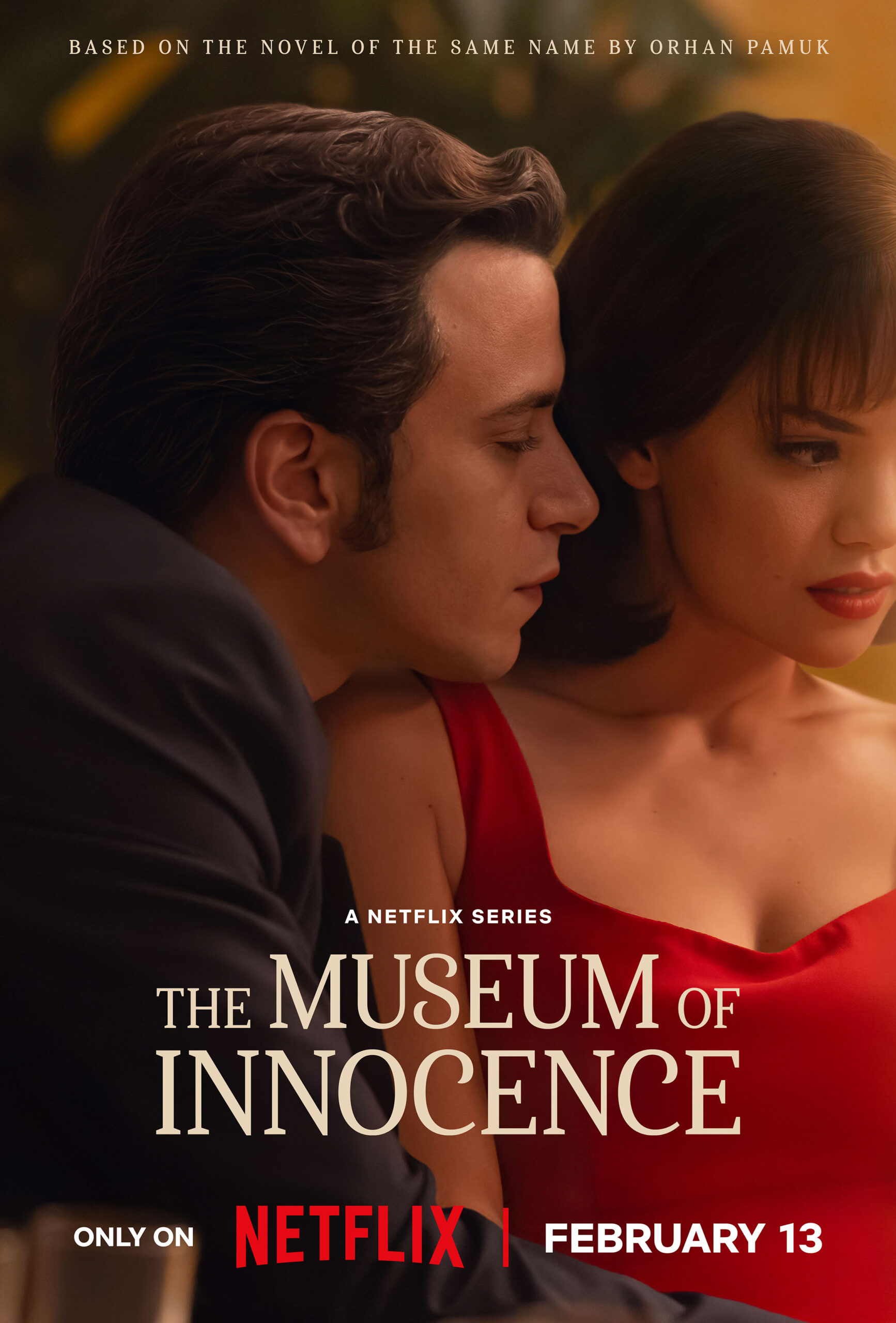

As Episode Magazine we spoke with Zeynep Günay, the director of The Museum of Innocence for our February 2026 issue.

It’s been about a year and a half since the shooting process ended, and when I look back at my memories from the set, I can’t remember the set itself; it feels like I’m wandering inside the novel. It’s as if Kemal and Füsun were real, as if all the locations were real, and as if we wandered through the novel together. This is something I’ve never experienced before, and it’s truly a strange feeling. It feels like we dove into the novel and then came back out.”

The Museum of Innocence is an important production as it is the first novel adaptation officially approved by Orhan Pamuk. Naturally, this approval brings with it a heavy burden and great responsibility. Although The Museum of Innocence is a text that is very open to adaptation as a novel, it is also a challenging work due to its layered structure, characters, symbols, and motifs.

However, it must be noted that Zeynep Günay, who has previously directed works such as Time Goes By, Bride of Istanbul, and The Club, has successfully shouldered this responsibility. Known as a director who embraces female characters and creates space for them in her work, it is also significant that Zeynep Günay adopts a similar stance in The Museum of Innocence series. Her portrayal of Kemal Basmacı as a human being with all his flaws, and her ability to articulate what Füsun and Sibel cannot express, are among the elements that set the series apart.

I spoke with Zeynep Günay about the challenges of adapting The Museum of Innocence, the production process, her communication with Orhan Pamuk, her approach to the characters, soundtrack choices, and details about the series. Enjoy the read!

I place The Museum of Innocence in a very different position among the recent domestic dramas I’ve watched. As an adaptation, it’s extremely well written and does justice to the novel. It’s also the first work whose adaptation Orhan Pamuk approved. How did the writing and production process unfold? Let’s start there.

Of course. I joined the project after a long writing process. By the time I came on board, the screenplay had already been completed, and the script written by Ertan Kurtulan had been approved by Orhan Pamuk. As someone who loves The Museum of Innocence novel, I was deeply affected when I read the script. It stayed true to the emotional core of the novel, was extremely faithful to it, and was written in a way that matched its depth.

The project was ready, but what I had to grapple with was the weight of directing the first novel adaptation ever approved by Orhan Pamuk. At the same time, we had limited time, and we took on a huge responsibility. We had a very short pre-production period. Due to the shooting schedule, for the first time in such an emotionally demanding project, I had to shoot all nine episodes out of sequence, intertwined rather than in chronological order. So we worked with all our strength in a very short time frame. Our shooting schedule was extremely intense.

It’s been about a year and a half since the shooting process ended, and when I look back at my memories from the set, I can’t remember the set itself; it feels like I’m wandering inside the novel. It’s as if Kemal and Füsun were real, as if all the locations were real, and as if we wandered through the novel together. This is something I’ve never experienced before, and it’s truly a strange feeling. It feels like we dove into the novel and then came back out.

You mentioned the weight of directing the first novel adaptation approved by Orhan Pamuk. Could you elaborate on this burden? What were the main concerns and points you focused on before stepping onto the set?

I first picked up The Museum of Innocence fifteen years ago purely as a reader, and I couldn’t put it down. There were moments when I went out to eat, forgot the meal, and continued reading the novel with great excitement. The bond I formed with the book back then was entirely a reader’s bond, independent of any idea that I might one day adapt it.

However, readers of The Museum of Innocence are divided into two groups. Alongside those who love it deeply, like me, there are also readers who approach the book critically because of Kemal or other characters. Ultimately, everyone who reads the novel has different ideas about love and the characters. Each reader attaches different meanings to it. Because I have formed a strong bond with The Museum of Innocence both as a text and as a museum, I felt a distinct responsibility.

I was also aware of those who approach the novel critically. Assigning meaning to a novel is one thing; visualizing and narrating it is another. Because when those meanings are visualized, they can become compressed within the narrative and may not fully find their place. I didn’t want that to happen. When I received the script, I had a clear path and knew the direction I wanted to go. Still, trying to tell a novel that evokes such varied emotions without reducing it to a single interpretation, without constricting it, and without losing the unique meanings each viewer could extract required a great deal of effort, and it scared me. This was something I experienced for the first time.

And you are a very experienced director with many successful works. How was your communication with Orhan Pamuk before going on set?

Thank you very much. I had very close communication with Mr. Pamuk. Before going on set, we met and had long conversations. We talked at length about the characters, the story, Nişantaşı society, and love. It was truly delightful and wonderful.

While watching the series, it’s very clear that it’s a work that was slowly matured and that Orhan Pamuk was closely involved. Beyond the screenplay, the art direction and visual language are also striking. The story begins in the mid-1970s, and the Istanbul of that period, along with details of old Türkiye, is vividly portrayed. How did you approach creating this visual language?

What guided me most in building this world were the objects Orhan Pamuk collected before writing the novel. The museum created from these objects and its connection to the novel deeply affected me. At the very beginning of this journey, there were objects. Mr. Pamuk built the novel around these objects. Therefore, I tried to remain extremely faithful to all the objects and items mentioned in the novel. Of course, I have very talented collaborators I’ve worked with before, including on The Club. I embarked on this journey with our art director Murat Güney and cinematographer Ahmet Sesigürgil.

Murat and I, in particular, have extensive experience with period dramas. That’s why we decided from the outset not to approach The Museum of Innocence strictly as a period piece. Although the story takes place in the 1970s and 1980s and the sociopolitical context of that era has a strong influence, at its core, Kemal and Füsun’s story is timeless. Therefore, we didn’t want to confine it within period drama conventions, we didn’t want to reduce it to that. That’s why the world we built mostly followed Kemal’s emotional state.

The first four episodes take place in Nişantaşı, where Kemal was born and raised but never truly belonged spiritually. However; from the fifth episode onward, as Kemal embarks on a journey of self-discovery, we also see other faces of Istanbul. We tried to associate Kemal with Istanbul and continue along that roadmap. Within a world woven around objects and the museum, we were careful not to let anything inorganic stand out.

The objects that define Kemal’s obsessive emotional state are what make the novel layered. There are also very important motifs and symbols in the novel, for example, the father motif. Where did you struggle most in using these motifs and symbols?

Yes, exactly. These are what give the novel its layers. When you try to convey a state of mind that spans pages of text through a fleeting glance or a brief moment, there are nuances that can be lost. To prevent such losses, we established certain codes. The “Jenny Colon” handbag, for instance, was used to define the theme of coincidence and what is real versus what is fake. Another important code was Füsun’s earrings.

Kemal’s tendency to collect stems from his mother. He creates a museum for himself in a house filled with unused objects. Kemal subconsciously chooses that space as a cocoon of love. That’s why we wanted certain objects in the apartment at Merhamet Apartments, where Kemal and Füsun’s love and intimacy begin, to feel like they were watching them. We coded these objects as social pressure. Something happening there despite society.

Since we’re talking about characters, let’s discuss Kemal Basmacı, the character who most divides readers. As the son of a bourgeois family trying to westernize, he is inward-looking, and this leads to constant confusion in his mind and emotions. In the novel, two women who suffer because of Kemal remain in the background and struggle to express themselves. As a female director, I felt you paid particular attention to this. What would you like to say about that?

Honestly, this isn’t specific to this project, I try to observe this distinction in every work I do. I try to approach my characters not just in terms of men or women, but as human beings. When portraying a person, you need to balance their dark and light sides. You need to tell the story from a complex place.

For instance, when I read the novel, I saw Kemal as extremely shy, observant, restless, unable to express himself properly, and unsure of what he was searching for. He is disconnected from the sociocultural environment he was born into, the Nişantaşı society, and his soul doesn’t belong there. Yet from the outside, he appears to have been born with a silver spoon, very fortunate.

Kemal is a character who, I believe, would have found relief if he could have been an artist. If he had a space to express himself, everything might have been different. That’s why I see him as more passive. He’s not an alpha, and he doesn’t deliberately lead women into chaos. I think Kemal is an innate manipulator, but not out of malice. He does it intuitively and genuinely doesn’t know what he’s looking for.

When he meets Füsun, this void begins to fill. He tries to find himself through this love, drifting along. He never acts in a planned or conscious way. His impulses are childlike. With his love for Füsun, his darker sides emerge, and that darkness leads him into an addiction he can’t resist. That’s how I see Kemal. It’s also the first time in my career that I’ve directed a work centered on a male character, so perhaps I perceived this balance differently.

Another challenge with such projects is casting, how characters are visually imagined. I found the entire cast very strong, not just Selahattin Paşalı or Eylül Lize Kandemir. How did the casting process unfold? Did you have any battles over casting as a director?

Of course! (Laughs) But I should say this: I read the novel fifteen years ago. I had a very short preparation period for the project, but the images related to The Museum of Innocence had been forming in my mind for a long time. So I already had certain images in my head. When I look at an actor’s face, I knew what emotions they need to make me feel.

Since this was Orhan Pamuk’s first adapted novel, I wanted to work with the best actors. I felt that responsibility, and I had very clear boundaries, not in terms of physical traits, but in terms of gaze and aura. For example, in the novel, Füsun’s hair is described as blonde in the early period. We didn’t just look for a blonde actress; we focused on the emotions those blonde hair symbolized. We sought the actor who could best convey those emotions.

It was a very challenging but wonderful process. I watched auditions from many young actors, including many trained performers who gave excellent auditions. For the first time in my life, I even watched fully produced auditions. I’d like to thank everyone who auditioned and our casting director Harika Uygur, who gathered so many auditions for me. The casting phase was truly intense and demanding.

I’d also like to ask about the soundtrack choices. Once The Museum of Innocence airs, everyone will start listening to Neco. Music choices are something I pay close attention to in domestic productions, as they can easily turn a series into a “music video” and disrupt the drama. That wasn’t the case here. The songs subtly serve the story and complete the emotions. You chose the songs yourself, right?

Yes, all of them were my choices. When choosing songs, I focus on what the subconscious calls forth. Pay attention to the song you hum to yourself after a bad day, or the one you sing in the shower after a good day. Your subconscious selects those songs without you realizing it. I allow space for that process. Usually, productions ask me to finalize music choices before shooting so rights can be secured, but I always leave this process until the final stage.

After the work has matured and I’ve focused on the scene, I want to see what fits. For example, Neco’s “Seni Bana Katsam” wasn’t originally one of the songs in my mind. It suddenly stood out in my 1970s playlist. The lyrics “If I added you to myself, mixed us a little, created a pair from the two of us” resonated with how Kemal manipulates Füsun, diminishes her, yet does so from a deeply romantic place.

The original of this song is French, À Toi. That’s why I thought it would suit Kemal, a character striving to westernize. “Seni Bana Katsam” felt like Kemal’s subconscious. I ran to the editing room and said, “Let’s try this song,” and suddenly it all clicked. Ultimately, my song choices aren’t about the scenes and how well they match those scenes, but about the characters’ subconscious and what they don’t openly show us.

Finally, if you were to adapt another Orhan Pamuk novel, which one would you choose?

I would love to adapt Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları (Mr. Cevdet and His Sons). It’s my favorite Orhan Pamuk novel. I would also love to adapt Snow, but Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları would come first.

The Museum of Innocence will premiere on Netflix on Feb. 13.